Kudos to The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) which has produced an excellent report into the use of consumer messaging apps within the Australian government. Based on a survey of 22 government agencies, it is one of the few quantitative research papers addressing the issue. Agencies that participated in the survey include Australian Federal Police, Department of Defence, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Department of Home Affairs and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

The report has led to independent senator David Pocock urging the Australian government to take action. The Guardian covers the story, which sees Pocock put forward strong probity and transparency arguments for keeping records of all communications related to government decision-making: “The use of messaging apps to deliberately avoid scrutiny through freedom of information is deeply concerning and will have long-term negative impacts for the health of our democracy, good governance, and the accountability of our decision-makers.”

That’s a pretty harsh, but fair, assessment. The path to enlightenment is always a tough one. Taking a serious look at the use of consumer messaging apps within the public sector is incredibly important. So full respect to the Australian Information Commissioner for making such an important contribution to the debate, even though its findings make difficult reading.

Please read the full report, but here’s a few highlights and our reaction to them.

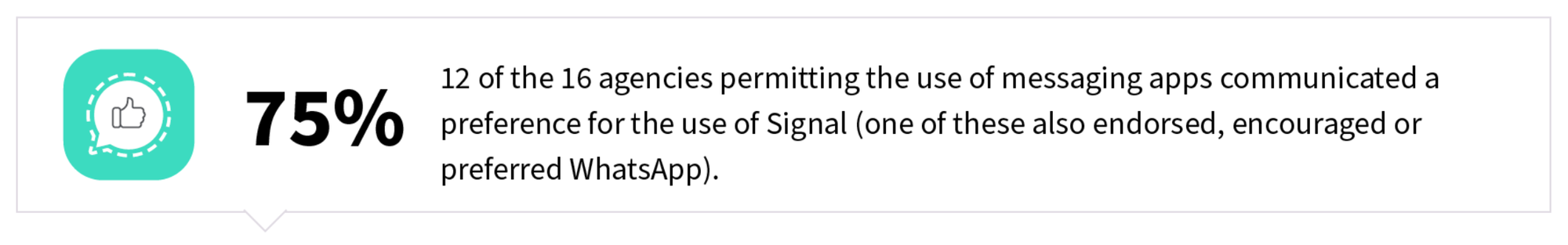

Messaging apps are an established feature of communications in the Australian public service. A surprisingly high 73% of government agencies (16 of the 22 surveyed) permitted the use of consumer messaging apps. Fourteen percent (3 agencies) prohibit the consumer messaging apps and the remaining 14% (3 agencies) did not have a policy.

Now, Signal is a great consumer application that puts a lot of thought into security and end-to-end encryption. It’s also open source, which ensures transparency of code.

But like WhatsApp, it’s a centralised US-based app that is not self-hostable and not open standard based. And in the case of WhatsApp, Meta can surveil the metadata of who talks to who in order to profile end-users for advertising and worse (remember we’re talking about agencies such as the Department of Defence, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet).

Perhaps one of the most obvious shortcomings of the use of Signal and WhatsApp within government - unaddressed in the report - is that because they are consumer messaging apps there’s literally no reliable way of ensuring who is in what group; the onboarding or offboarding of joiners and leavers and authenticating those in groups chats. That problem grows exponentially when communicating across multiple government departments (or between governments), particularly on sensitive matters. There’s absolutely no way that can be left to chance; it has to be managed through a formalised IT function, and ideally by utilising existing sign-on systems.

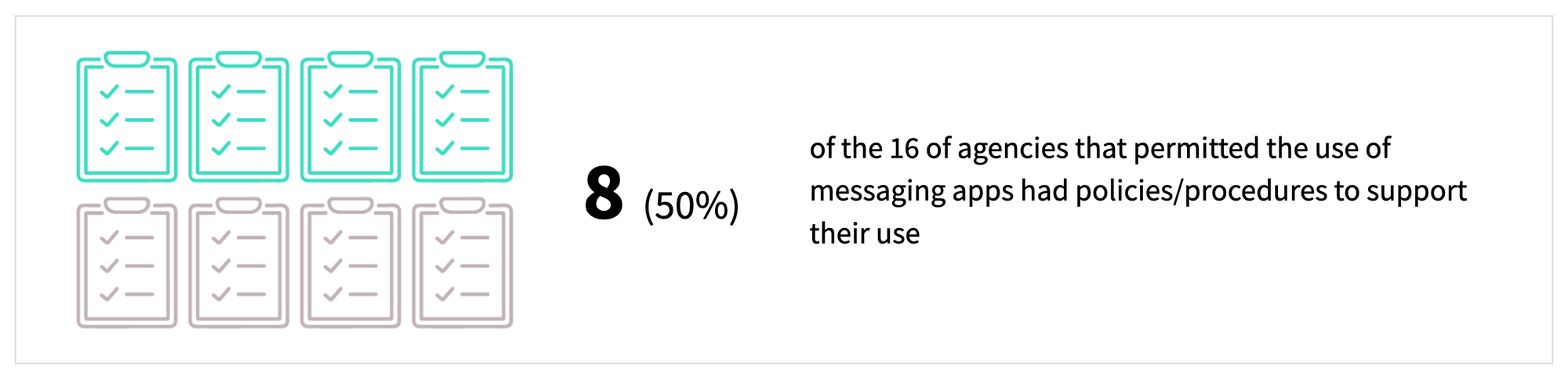

Paucity of policy and procedures

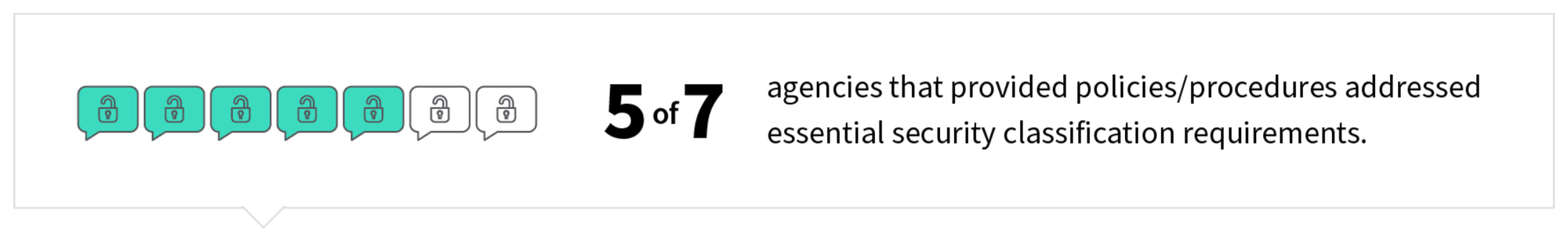

Of the 7 agencies that provided their policies or procedures…

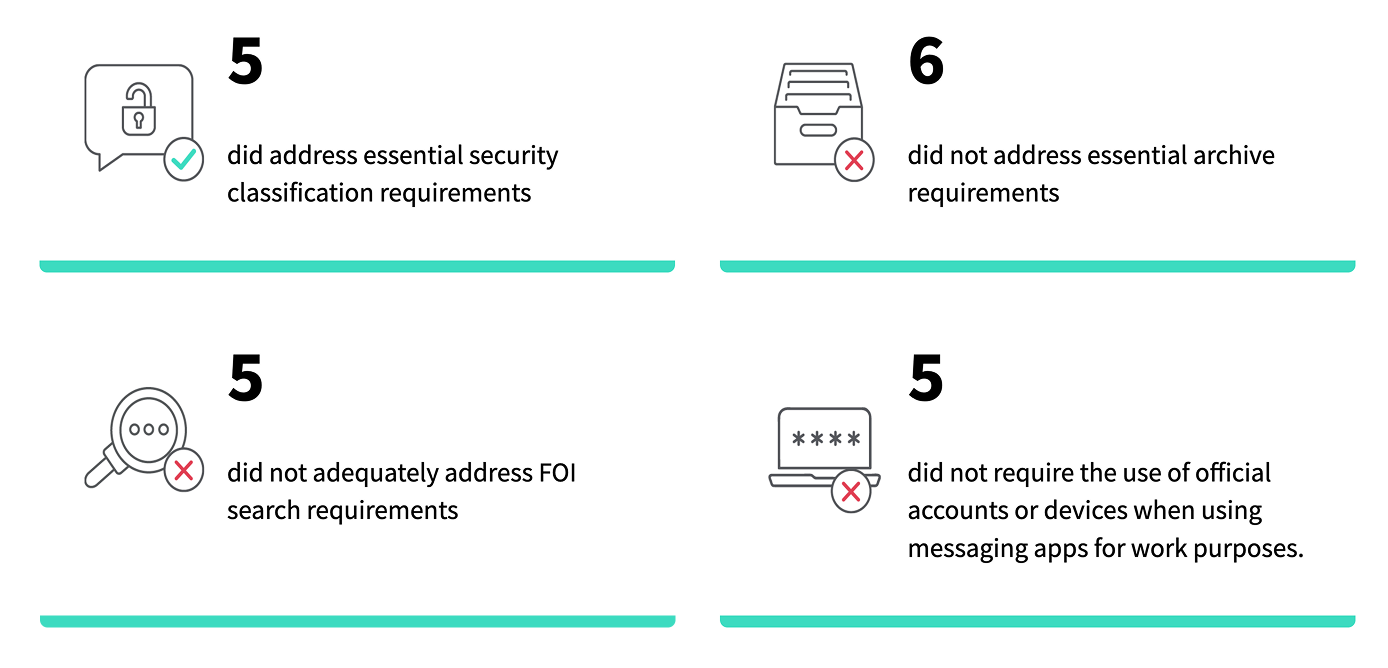

That policy and procedures are only in place for half of the agencies that permit the use of consumer messaging apps is a concern. However the more notable finding is that the policy and procedures that do exist miss key requirements. The two most interesting policy areas relate to archiving and security. Procedural detail around archiving is understandably light, given that consumer messaging apps don’t support the formal record keeping required within the public sector. When it comes to security, it seems that little thought has gone into anything beyond the app’s end-to-end encryption.

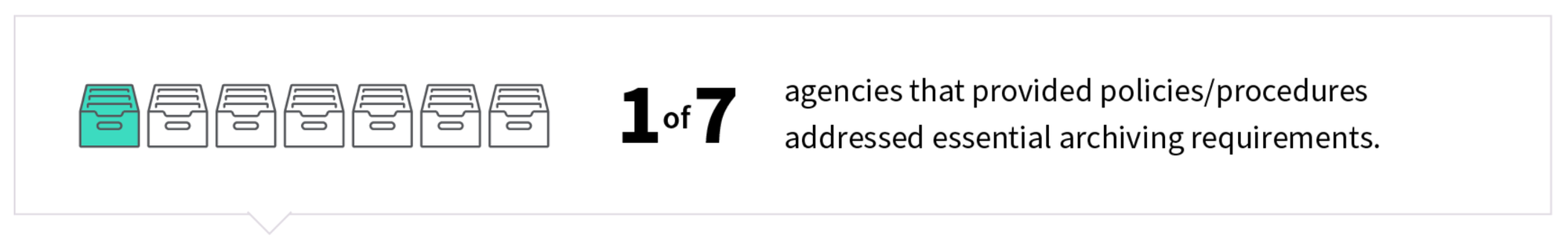

The one agency that advised how messages are to be extracted from a messaging app to its record keeping system stated that a screenshot may be a means of extracting information. This agency is described as being “very large” which, according to Appendix A: Methodology, means it has to be one of the Australian Taxation Office, Department of Defence, Department of Home Affairs or Services Australia.

If you find it concerning that one of these agencies is attempting the record keeping of official government conversations in consumer messaging apps by screenshotting from mobile phones, remember the other six agencies with a policy on archiving give no suggestions at all. And that the 15 other agencies in the report don’t even have an archiving policy in relation to messaging apps.

As with any consumer messaging app, Signal and WhatsApp have no record keeping which breaks all sorts of compliance requirements. Public sector organisations need to be accountable, so there has to be a record of discussion and decision making. It is of course critical for communication to be end-to-end encrypted, but that shouldn’t mean there should be no option of an audit trail when required.

Of the 5 agencies that addressed classification in their policies and/or procedures, all encouraged, endorsed or preferred Signal.

Two of these agencies allowed the use of Signal for materials classified as PROTECTED and below. Two allowed the use of Signal for materials classified OFFICIAL: SENSITIVE and below. One agency allowed the use of Signal for documents classified as OFFICIAL and below.

Now this is really quite concerning. Setting aside the issue of managing users (leavers, joiners, authenticating new invitees; generally being sure the right people - and only the right people - are in a particular group chat), Signal only works through a central server and cannot be self-hosted in a decentralised environment. It means that all the Signal servers sit in the cloud within the boundaries of U.S. jurisdiction. Even if a government trusts that Signal’s encryption is great, and the U.S. administration cannot listen in, it could still require Signal to block communication - as the Trump administration just did with Microsoft services for the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Signal’s centralised design also leaves it vulnerable to attacks on the central infrastructure (it’s a hugely attractive honeypot), and there is no way to operate Signal in secured or air-gapped networks. In the case of a real crisis, where undersea fibre cables are cut and satellite bandwidth is limited, it’s unclear if its servers would even be reachable. In short, Signal doesn’t deliver digital sovereignty.

Recommendations from the Australian Information Commissioner

The report gives four main recommendations to help agencies better meet their recordkeeping, freedom of information (FOI) and privacy obligations when using messaging apps.

We’d suggest agencies go further. Messaging apps are incredibly convenient and aid productivity. The trouble is that consumer messaging apps are not fit for purpose. Rather than developing policy and procedures for flawed products, agencies should provide their employees with messaging apps designed for the public sector.

This is driven by records management requirements. By self-hosting its own solution, a government agency can benefit from the protection of end-to-end encryption while retaining oversight and control; from record keeping to managing users through existing authentication systems and single sign on systems.

There’s a reason why smartphone users don’t default to Microsoft Teams, Webex, Slack or other corporate apps. To be successful, an enterprise-grade messaging app has to be as simple to use as a consumer messaging app. It’s why we put so much effort into making our app so easy to use whilst simultaneously offering powerful enterprise features from the server-side.

It’s also why we put so much effort into the Matrix open standard; to ensure the interoperability that is absolutely critical for communicating across and between government departments. Think of Matrix as the real time communications equivalent of SMTP for email. It enables separate and sovereign deployments to federate, even if they are using different Matrix-based clients (in the way that it’s common for people to email each other, despite using different email clients).

It’s a good point. It’s why Element can be used within the workplace without revealing the end-user’s name, telephone number or other contact details.

Recommendation from Element

Governments should ban the use of consumer messaging apps for use within the public sector, and instead provide an equally usable messaging app that also provides the oversight and control government agencies need to ensure responsible use and compliance.

They should look for an enterprise-grade solution that provides a government agency with its own digital sovereignty. A decentralised technology brings tremendous benefits in terms of an end-user organisation being able to own, host and control its solution and data, and ensures more robust and reliable communications even in moments of crisis and break-down of intercontinental connectivity.

Open source software provides complete transparency. Choose a popular open standard, with a healthy competitive ecosystem to protect against vendor lock-in, to ensure the interoperability that is critical for communicating across and between government departments.

End-to-end encryption is essential, but basic table stakes. As is the ability to identify, authenticate and manage users. And of course, such a system should be fully managed and maintained to ensure it’s continuously stable, updated and secure with guarantees provided through a robust service level agreement.

The question is not how to manage the use of consumer messaging apps within government. The question is “Why isn’t government embracing a new era of sovereign, secure and interoperable real time communications?”

For more insights into real time communications for government use, download our Future of Secure Communications study from Forrester Consulting.