The Swedish Armed Forces (Försvarsmakten) has announced it will standardise on Signal for all non-classified communications via mobile devices. Signal has a strong security posture, encompassing end-to-end encryption, minimal metadata, and other privacy-preserving features.

The decision underscores an ongoing shift among military and government entities worldwide towards adopting end-to-end encrypted communication solutions to protect unclassified yet sensitive exchanges.

In many ways, it’s a sensible move from Försvarsmakten. The geopolitical landscape has changed in a short space of time, and embracing Signal is more practical and secure than telephony, SMS, Skype or other insecure communication solutions. Signal has also been embraced within the European Commission, and other European governments.

But in all those cases, let’s be honest, it’s more of a convenient quick fix rather than a strategic initiative. Signal is a privacy-centric platform for consumers. It is simply not designed to handle the official and often legally mandated needs of government and defense bodies. Being a centralised design, Signal is vulnerable to global outages and being blocked - similar to WhatsApp, Microsoft Teams and other traditional cloud based services.

From a geopolitical standpoint, Signal is also run from the US, using US cloud providers and backed by US government and philanthropist funding; all of which raise concerns over US influence and data sovereignty.

The need for accountability

One of the challenges for an Armed Force, indeed any organisation, is to address the use of unsanctioned technology - known as ‘shadow IT.’ When it comes to messaging apps, there are a number of related issues. Not all messaging apps provide the security expected (Telegram for instance, isn’t end-to-end encrypted unless you use ‘Secret Chats’, which only support DMs). WhatsApp can collate user data with other Meta products and doesn’t encrypt metadata. Different apps do not interoperate (for instance, a Signal user can’t message someone using WhatsApp) in the way email does, creating communication silos.

Let’s not forget, all of these solutions are just consumer apps and sanctioning their use muddles the line between personal and work-related communication. It’s effectively the same as telling government employees that it’s OK to go wild with their personal Gmail or ProtonMail accounts for official government communication.

However, the biggest issue for an organization like the Swedish military is that there is no oversight or control over employees using Signal (or any other consumer messaging app), unlike traditional email or military communication tools. For example, there’s no identity and access management to support Single Sign-On systems. This creates vulnerabilities in managing personnel changes, ensuring classified discussions remain secure, and preventing unauthorized individuals from accessing critical information. The UK's recent public outcry over the COVID inquiry’s vanished WhatsApp messages illustrates the dangers of using consumer apps for official communication.

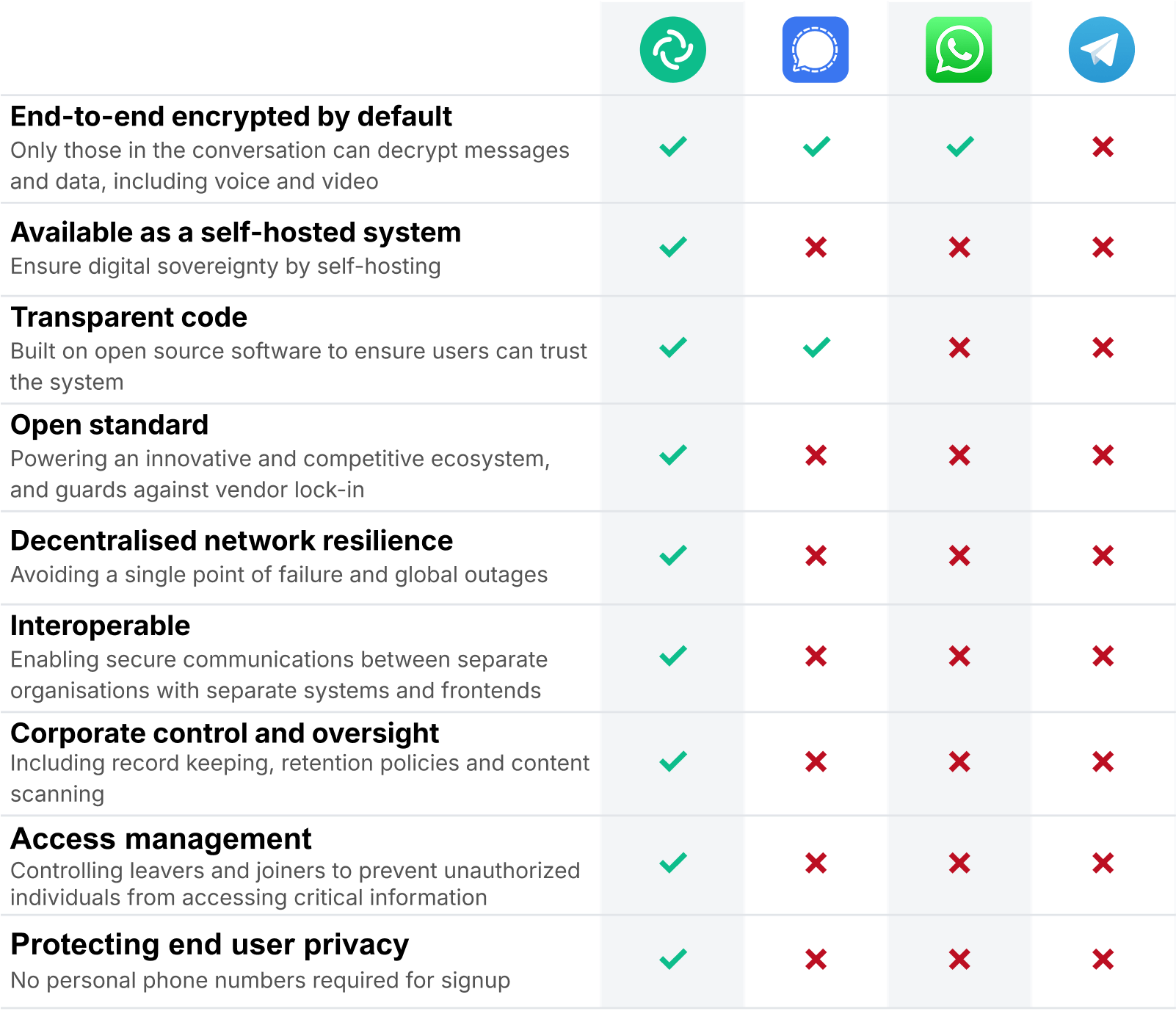

Element compared to mainstream consumer messaging apps

Conflating privacy with security

Military communication demands more than just privacy. When necessary, it requires audit trails, robust archiving, and the ability to retrieve information, often years down the line. These are not features typically prioritized in consumer messaging apps. In fact, they often run counter to the core principles of such platforms, which emphasize user control and data minimization.

The Swedish Armed Forces’ decision inadvertently conflates privacy with security and accountability. While privacy is undoubtedly a crucial component of secure communication, it’s not the only one. Security, in a military context, encompasses a broader range of considerations: sovereignty, end-to-end encryption, accessibility, interoperability, and long-term preservation. A truly secure system for military communication must balance the need for confidentiality with the imperative for operational requirements, transparency, and accountability.

The single point of failure and the need for decentralisation

Reliance on a single centralised platform such as Signal creates a significant single point of failure. Bad actors could easily target the platform at a critical moment, leaving Sweden’s defense forces without a reliable means of communication.

Moreover, the signature of the network traffic when communicating with Signal’s centralised servers is obvious to any sophisticated attacker, easily identifying Signal users. Similarly, simply scanning a country’s phone number range for Signal-enabled numbers and geolocating those handsets via SS7 could be a viable attack..

The history of cybersecurity is filled with examples of even the most secure systems being compromised. Depending solely on one consumer-grade app increases the risk of a catastrophic data breach or outage.

A more robust approach would involve adopting a decentralised standard for real-time communications that ensures interoperability and network resilience. This is, of course, what the Matrix open standard provides and why so many governments are turning to Matrix-based systems.

Connecting with partner forces

The Swedish Armed Forces’ decision to adopt Signal also raises concerns about interoperability. Military and defense agencies must communicate seamlessly with allies, and relying on a single platform can create barriers to communication with those using different systems. Especially if a service does not operate in an allied country for whatever reason.

Again, Matrix provides a more effective approach, ensuring that defense agencies can control their own communications while still maintaining seamless interoperability with their counterparts. Each partner force can even create its own Matrix-based frontend, such as The Bundeswehr’s BwMessenger, or NATO ACT’s NI2CE Messenger.

Private federation between separate systems can be further secured through the use of secure border gateways, and interop with high-side environments can be supported through the use of hardware based cross-domain gateways. Likewise server-side content scanning can protect against cyberattacks by optionally inspecting data in a trusted self-hosted environment on the server-side.

Finally, Signal is a closed platform. It does not allow 3rd party apps, bots or clients to connect - and interoperability with 3rd party systems is forbidden. So if you wish to exchange data with third party systems (e.g. Tactical Data Links; Cursor on Target messaging; situational awareness apps such as ATAK), you need an open platform built on an open standard instead.

A call for strategic solutions, not quick fixes

The use of an end-to-end encrypted communication solution is, of course, essential. But in an era of increasing surveillance and cyber threats, this is just table stakes. Simply adopting a readily available consumer app is a superficial solution that fails to address the complex security and governance challenges inherent in military comms. Particularly in the context of evolving transatlantic relations, and the need for greater European self-reliance on the technical side.

Genuine security requires a holistic approach that considers not just encryption but also data governance, accessibility, interoperability, and long-term preservation.

It also involves a fundamental principle crucial to any national defense entity: sovereignty. This means having technological independence and using technology that the end-user organization owns and manages.

Governments and militaries need to host their own communications platform, rather than rely on a cloud service that is controlled by a vendor headquartered in a different country and therefore subject to another government’s political whims.

Digital sovereignty is aided by open-source software, which allows for independent inspection, security validation and supports a competitive marketplace to guard against vendor lock-in.

Done properly, a sovereign and secure messaging solution can easily support use for classified information; whether that’s for a nation’s military, pan-government or at an intra-governmental level.

Remaining in control

True digital sovereignty keeps a nation’s real time communications secure and continuously available.

While the Swedish military advocates for end-to-end encryption, Sweden’s law enforcement and security agencies are pushing for legislation to create backdoors in end-to-end encrypted messaging apps. Just two days after the Swedish military announced its decision to standardise on Signal, the messaging app indicated its willingness to withdraw from Sweden if the nation’s proposed encryption-busting laws take effect - demonstrating how relying on a centralised foreign service for internal communications presents risks.

We applaud Signal’s resolve to let itself be blocked rather than conform with an encryption backdoor in particular markets, much as Apple has done with ADP in the UK. Element would take the same action if forced.

But of course, with a self-hosted system based on open source software, an organisation would remain in full control of its platform regardless of the vendor.

Ensuring the control to self-determine outcomes is military thinking. However convenient it might be to pick an app, the real task is to formulate a strategy that ensures communications remain sovereign, interoperable, resilient, and secure.